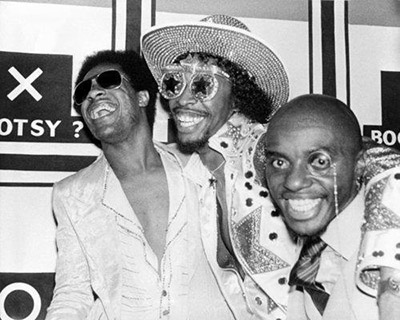

Original vocalist of the Bootsy’s Rubber Band and the P-Funk galaxy, Gary « Mudbone » Cooper looks back at his unique career featuring George Clinton, Bootsy Collins, Prince, Dave Stewart and many others.

★★★★★★

Funk★U : What was your first musical memory?

Gary Mudbone Cooper : My first musical memory was when I was three years old. At the time, we lived in Baltimore in a three-story house. My mother’s next to oldest sister, aunt Lucille lived on the first floor, my mother, father, and I were on the second floor, and my mother’s younger sister Ann was on the third floor with her two sons. Every morning I would go downstairs to see aunt Lucille, who would make me pancakes. She made pancakes for me everyday because I loved them. It was like a religious ceremony and she would always sing along with the Gospel songs playing on the radio. She loved and only listened to gospel music, and that’s when I first heard Mahalia Jackson, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and all the other gospel singers and groups.

One morning, while auntie was making them good ole pancakes I started singing with her. She stopped with a surprised look on her face and said to me, “Gary, you have a beautiful voice! Will you do me a favor and go sing at Church with me Sunday?” I replied to her, yes ma’am! She said I’m gonna tell Ruth, my mother her sister, and we’re going to buy you a nice suit to wear. So the next Sunday I sang in public for the first time in church. I remember the people there were

very emotional. Some were crying, and since I was three years old, I wondered if I had done something wrong (laughs)… Around the age of seven or eight, I joined the teen choir, and then the adult choir when I was a teenager. Around that time, I also started singing in a local band in East Baltimore called Ricky and the Chips. I must have been twelve or thirteen. Ricky was the leader of the band, which his parents managed. I sang and imitated James Brown, and I was so

good at it that everyone in Baltimore called me Baby James Brown.

Ricky and the Chips often played outdoor events and street concerts, and sometimes for a community program called Operation Champ. We played on the back of a wide truck and gave out free meals to the community. One day, James Brown came to play at the Baltimore Civic Center (in 1966, editor’s note), and Maceo Parker saw us playing on the street. He introduced himself to us, told us he was in James Brown’s band, and he congratulated us, and invited us to the concert. A few years later, I played at the Civic Center with the band The Civics, which also featured Robert « Peanut » Johnson. The Temptations and Stevie Wonder were headlining, and during our concert, I got to do my Baby James Brown number and got a standing ovation.

In Baltimore, there were a lot of musicians like Dennis Chambers and Rodney « Skeet » Curtis, Chester Thompson etc. I didn’t know them, but they all knew who Baby James Brown was. We were very popular, and our show was patterned like the James Brown revue. I had picked up his body language and his dance moves from seeing him at the Apollo. I had the costumes and everything. When I was in the Rubber Band, I was in my element, because it was 70% JB’s with Bootsy, Catfish, Frankie « Kash » Waddy, Maceo Parker, Fred Wesley, and Richard “Kush” Griffith, while Joel « Razor” Sharp » Johnson (keyboards, ed.), Robert « Peanut » Johnson and I were from Baltimore. Rick Gardner (trumpet) had played in a West Coast band called Chase.

In Baltimore, I had opportunities to play in a lot of different bands. After being Baby James Brown, I joined the Jetsons, an all-white band from Essex, Maryland. They were top notch musicians and the first band I made impressive money with. They covered Otis Redding, James Brown as well Chicago and Blood Sweat and Tears. They were great musicians. I learned a lot from them. Working with the Jetsons helped me realize that music had no barriers. After them, I joined

Madhouse, an all-black band that played awesome and very theatrical with costumes. I would come on stage in a coffin and we would cover YES songs on stage like « Roundabout » and « Close to the Edge. » Our versions really rocked! We wrote/played originals, and a really unique cover of the Stylistics song “People Make The World Go Round”, that truly wooed every audience we played for. Our performance positioned us to be in demand to open for major act like Ohio Players, War, Funkadelic, Barkays etc. When I became a member of Bootsy’s Rubber Band, Parliament/Funkadelic, George Clinton asked me to recruit him a bass player and drummer. I contacted Bunky, Madhouse bass player to join Parliament-Funkadelic, but he wasn’t interested. Then I contacted Rodney « Skeet » Curtis, who I knew, went to school with and did some things with and he was perfect!

How did you get into Bootsy Collins’ Rubber Band? ?

In 1973, Bootsy and Frankie “Kash” Waddy picked me up in Baltimore and moved me to Cincinnati. Upon arriving, I was surprised to find that Bootsy was living with his mother. I had seen this guy play with James Brown, which was huge at the time. and I started wondering if I was making a mistake moving to Cincinnati, because I was leaving my parent’s home in Baltimore to go pro. We got to work right away, started going to the studio to record demos and one of the first

collaborations was “I’d Rather Be With You”, which Bootsy had started with music and verse melody, and I created the chorus/hook melody. That was the first time I ever doubled my own harmony vocals on a studio recording for professional purposes. We did several other demos like “Say Something Good”, “Together In Heaven”, “Love and Understanding” etc…

You’ve also had the idea of Bootsy’s famous star glasses…

Oh yeah. That was right before we recorded “I’d Rather Be With You.” One night, I went to use the bathroom at Bootsy’s mom’s house. When I was going back to the room I was sleeping in, he wanted to show me something. He said, “Hey, man, look at this.” On a piece of paper, he had drawn a bass guitar in the shape of a star. I told him that was really cool, and when I went back to my room, I took a piece of paper and drew a pair of glasses in the shape of a star and I showed it to him, and there it was… Later, I mentioned to him that he never mentioned that in any interviews, I never got anything. This is one of a few disappointments

I’ve had to endure in the music business, which is often very unfair for many.

Do you remember your first meeting with George Clinton?

We opened for Funkadelic in Baltimore with Madhouse. After the show, George came up to me and said if he didn’t know what band he was in he’d swear he was in our band because, he really liked our performance so much. I thanked him for the compliment and said, “If you’re ever looking for a singer, here’s my number.” The first time I recorded with George was for Parliament’s Chocolate City album, which was pretty much the same time as Stretchin’ Out in a Rubber Band was recorded. Bootsy, Catfish and I had a song called “Together in Heaven,” under the name of Bootsy, Phelps And Gary, which ended up on the album as “Together.” It was on Chocolate City. George asked me to play drums on The Mothership Connection album, the song “P Funk Wants to Get Funked Up”. At first I thought he was joking. We were at my dad’s house smoking some weed and stuff, and at one point I started beating on the table. George said to me, “Man, why don’t you play the drums?” I said, “You must be stoned, I’ve never played drums in my life!” He said all I had to do was play the rhythm I was tapping on a drum kit, and it came out as “P-Funk (Wants to Get Funked Up).” I had never played drums in my life, or taken a lesson, but when I was Baby James Brown, I had to emulate James Brown’s timing, he was the best in the genre. So after I was Baby James Brown, I worked with a lot of the JBs. I even recorded once in the studio with James Brown and George. It was in Tennessee. Mr. Brown came into a P Funk session and we recorded some vocals together!

So you recorded with George before you went on stage with Parliament-Funkadelic?

Exactly. When I started working with George, the original Parliaments were still there. The only original member of Funkadelic that wasn’t there was, Tawl Ross. Parliament’s music was changing with songs like “P-Funk (Wants to Get Funked Up)” and later “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker).” That’s one of the things I brought to the band, and we sang great harmonies with Garry Shider. On the first Bootsy’s Rubber Band album, Peanut is credited, but he

doesn’t sing on this record. It’s me, Bootsy, a girl named Leslyn Bailey, and Garry Shider on vocals. With Garry, we sing on “Another Point of View,” on “Love Vibes,” it’s me and Leslyn, and the backing vocals at the end of the song are me, Garry Shider, and Glenn Goins for the first time. Of course, it’s Bernie Worrell on keyboards, although Razor Sharp is credited. There was also another guy on keyboards, Fred Flintstone, who I brought back from Baltimore. Cordell Boogie Mosson plays drums on “I’d Rather Be With You” and “Vanishing In Our Sleep.” I also play drums on “Another Point of View,” and Bootsy on “Stretching Out,” I think. I also play on a lot of other songs, including “Can’t Stay Away,” “What’s a Telephone Bill?”, “Night of the Thompasorus People,” “Liquid Sunshine,”

Parliament’s “Aquaboogie,” Bernie Worrell’s “Insurance Man for the Funk,” Parlet’s “Mr. Melody Man,” and “Ridin High”, Brides of Funkenstein’s “When You’re Gone,” “Take My Loving”, and“Atomic Dog,” among others…

What did a recording session with Parliament-Funkadelic looked like?

It was very organised, very professional. I see it this way: to some people they might have seemed chaotic, but there was a budget and a certain stake in these sessions, and even though there were loads of musicians in the studio, some of them extravagant looking, everyone gave their all and it often resulted in very good music.

What are your first big touring memories?

The Rubber Band were touring with Parliament-Funkadelic in the 1970s, and our manager had advised George and Bootsy to headline their respective tours. On stage, we gave George a hard time. The Rubber Band was serious business. My first big tour was with Bootsy’s Rubber Band. It was around 1975 and we had come to England. The press there wrote that Bootsy was the Jimi Hendrix of bass. Funkadelic had already come before us, but the press was very excited and we had also done some shows in Germany. The next eldest, in 1976, a young musician who was then unknown came to see us at our hotel after a concert at the Fox

Theater in Atlanta. Every night, after each show, we used to meet up to discuss the concert with the band. That night, there was a knock on the door and I went to open it. I discovered a kid who asked me shyly if he could see Bootsy. I come from the streets of the East Baltimore neighborhoods and I was used to deals. Sometimes, there would be a knock on the door: « I’m here to see Big John. » « Who wants to see him? » « Tell him it’s Little Willie. » « Big John, a

motherfucker named Little Willie wants to see you. Shall I open it? OK, come in… » (laughs). I did the same thing with this kid who said his name was Prince. Bootsy let him in, and Prince asked him a few questions about the record industry and touring, and then he left. As he left, he thanked Bootsy, and then he thanked me for letting him in. No big deal, man. I had no idea he was going to be such a motherfucker… A few years later, in 1983, we recorded

the album P Funk Live at the Beverly Theater Hollywood. I was backstage, getting ready to go onstage to sing “Red Hot Mama.” Ron Ford (backing vocalist for the P-Funk All-Stars) was with me, and we heard someone say, “Where’s George?” I turned around and it was Prince. I asked him why he was there, and he said he was just checking out what was going on. Ron told him: « Don’t move, motherfucker, you’re going to get your ass kicked! » (laughs).

You are credited on Prince’s album Graffiti Bridge (1990). What was your contribution?

I was in a studio with George in Detroit, and Alan Leeds, who was Prince’s tour manager, was there. When I arrived, they were listening to a playback together. I asked Alan what it was, and he told me it was a new Prince song, and then he said, “He sent me here because he wanted you to play drums on it.” I asked him who was playing drums on the song we were listening to, and he told me it was Prince. I was surprised that he would ask, but that’s how I ended up playing the part of “We Can Funk.” I didn’t question it, and you can’t refuse Prince anything (laughs)!

You did the legendary Earth Tour with Parliament-Funkadelic, which is one of the biggest tours of all time. What do you remember about it?

It was a huge tour, with the Mothership on stage and a bunch of other stuff. The whole music scene was watching us, including rock bands like Electric Light Orchestra who also had their flying saucer on stage. On our side, everything seemed normal. We didn’t think about all that, and George was in great shape, funny as ever. “Earth, hot air and no fire” (laughs). At the time, the only band that had a bigger live production was Kiss, who had more money than the

Rolling Stones, but seeing Parliament-Funkadelic on stage with Boots’s Rubber Band was huge. Sly Stone was there too, not with the original Family Stone, just with Cynthia Robinson. Sly had me on the right track, and I finished the tour in his tour bus. I first met him in 1970 somewhere in Louisiana, and I remember taking pictures of him with Dawn Silva and Lynn Mabry during the Earth Tour…

This grandiose tour, however, marked the end of the great P-Funk era, as if it had collapsed under its own weight.

That’s true, and I ended up walking away from P-Funk in 1979, just after Aquaboogie came out, which had gone to number one. We had a huge show at the Coliseum in Los Angeles. Everyone had come, even Michael Jackson was backstage. The next morning, I got on the first plane to Cincinnati and I left show business… Things had changed, and I didn’t see Bootsy and George the same way anymore. Plus, I had other offers lining up: Rick James wanted me in his band, in fact, Jeffrey Bowens from Motown wanted to sign the Rubber Band before Warner Bros., and they approached him around the same time. Heart, the Wilson

sisters’ band, had also called me. Frank Zappa wanted to recruit me, Garry Shider and Glenn Goins to be part of the Mothers of Invention. Later, Maceo asked me to replace his son Corey, but I couldn’t see myself wearing a suit and tie every night (laughs)! Roger Troutman also asked me to join Zapp, but their show was too repetitive and meticulous for me. I didn’t want to do the same thing every night. One day, Stevie Wonder sent two girls to pick me up at my hotel. They took me to Stevie Wonder’s house, and he said, « Mudbone, I love your voice. Come sing with us. » I said, « Stevie, I really feel sorry for you, but right now I feel like I’ve lost my

soul. I need to go home and find myself. » Stevie said he understood.

I didn’t want to hear about show business anymore and I went back to church and studied the Bible. I got a job in telemarketing, and I learned a lot about sales. I did that from 1979 to 1981, and one day my boss came up to me and said, “I’ve got George Clinton on the phone. He wants to talk to you.” I asked my boss what I should do, and he said, “You should talk to him. We know where you’re from.” I picked up the phone, and George was on the other end of the line with Mallia Franklin: “Hey, man, we got a new song. Meet us in Detroit!” I told him I didn’t want to, that I was happy with my new life because I didn’t have any drug

problems or money problems. George said, “I promise you, things will be really different this time.” » I didn’t give my answer right away, but I finally accepted because my boss had promised to rehire me if things went badly in Detroit. He had even offered me the position of regional manager, with all the perks that went with it: better pay, a company car and everything that goes with it…

So I went to Detroit, and George’s new song was “Atomic Dog,” on which I played drums and did backing vocals. At the time of recording, George had locked himself in a hotel right across the street from the studio for three days. He was afraid to leave his room. When he arrived at the session, he looked like he had just partied with the devil. He was completely wasted, but when he started to hear the playback of the song, he suggested some ideas. David Spradley, who was playing guitar, had the idea to play the music backwards, Garry Shider laid down the vocals, and Dennis Chambers played a drum part. When George listened to his

part, he wasn’t happy with it. He said, « There’s a breath missing between the snare and the kick”. Then I recorded the drums from top to bottom of the song, adding a breath on the hi-hat mic as I played and recorded, the rest is Funky History!

At that time, you launched two solo projects, Gary & Garry and Sly Fox, with the single « Let’s Go All the Way ».

In Detroit, I met Ted Currier, the manager who had managed to get George Clinton a record deal, when no one wanted to hear about him at the record companies. At my first meeting, Ted asked me what I wanted to do. I told him that I didn’t want to do what I had done with George and Bootsy. I didn’t want to start a band either, but I would prefer the idea of creating a duo. At that time, most of the successful artists were created for marketing reasons, like

Michael Jackson and Paul McCartney, or Dionne Warwick and the Bee Gees who were always on MTV. I said to Ted Currier, « Imagine the singer from Parliament-Funkadelic and the singer from Bootsy’s Rubber Band together. » He was thrilled and came back the next day with an $8,000 budget to record a two-song demo. That’s how Gary & Garry was born, with Garry Shider. We recorded two songs at United Sound Studios in Detroit, « Dance Rockit » and « Satisfied, » with David Lee Spradley, Eddie Hazel, George, and Mallia Franklin.

Shortly after, Capitol Records offered us a huge deal, even bigger than the ones George had managed to get for Bernie, Eddie, Bootsy, although they never got the money we offered them because George had taken pretty much everything for himself, paying everyone else only what he wanted to give them. When George saw the amount Capitol Records offered us for Gary & Garry, he went crazy. But behind the scenes, Nene Montes [George Clinton’s manager at the time, editor’s note] torpedoed the contract with Capitol, and the deal fell through. I said to Garry, « I love you like a brother, but I’m not going to pass up this deal. » Then I talked to Ted Currier, who didn’t know what to do because Capitol didn’t want us anymore. I told him that we had to go all the way (« let’s go all the way », editor’s note), then I hung up, and I took out a little dictaphone, I sang a melody and came up with a beat, and it didn’t take me five minutes to write a song. I called Ted back, I played him my demo, and he offered to go into the studio without even recording a demo. I ended up in New York and we recorded “Let’s Go All the Way,” and I knew right away that it was a hit, and it was (released under the name Sly Fox, a duet with Michael Camacho, the song went into the US Top 10 in 1986, editor’s note). I still get royalties from it today, and even more than I did from “I’d Rather Be With You,” because “Let’s Go All the Way” has been used in several films, and in the soundtrack for the game Grand Theft Auto. It was also covered by an English band, Sugababes, and Robbie Williams in the soundtrack for Iron Man 3.

This begs the question: with the exception of George Clinton and Bootsy Collins, how do the historic P-Funk musicians make a living from today?

Peanut and Garry Shider had a little bit of royalties on a few songs, but the sad reality is that the day George is gone, all the musicians still in the band will get nothing. I figured that out a long time ago… Garry Shider didn’t get what he should have gotten, Bernie Worrell and Eddie Hazel didn’t either. Billy Bass Nelson was never credited for coming up with the name Funkadelic, and he was largely responsible for the band’s formation. Same thing with Bootsy for “I’d Rather Be With You” and his glasses, but I don’t have a problem with that because I know the truth. I never depended on Bootsy or George for work. I enjoy playing with them, but I can do without them and I always know which way to go.

Among your many sessions in the 1980s, we also hear you on songs by the Ramones (on the soundtrack to Pet Cemetary, 1989) and Jack Bruce for his album A Question of Time.

Bernie Worrell had introduced me to Jack Bruce, with whom he was recording in New York. I met him while recording A Question of Time, then we went on the road. On that tour, Ginger Baker was on drums. He had a reputation for being uncontrollable, but everything went well between us. He called me “Mudpie”, and I remember that he hated the guitarist who played with us, Blues Saraceno. He kept saying: “that guy is not Eric”, thinking of Clapton. One night, on stage, Ginger Baker waved at me and said “look what I’m going to do”. While he was playing, he balled up a drinking cup and batted it with his drumstick straight tothe back of Saraceno’s head in the middle of a solo. He turned around, furious, but Ginger kept playing like nothing was wrong (laughs).

He was crazy, and he was on a lot of drugs, but he was a really nice guy outside of it. He came over to my house a few times, I introduced him to my family and we had a great time together. He was very laid back, and one day he told me it was good for him to spend time at my house. Eddie Hazel had also spent some time at my house, shortly before he died. One day we were in my living room, and he started crying. I asked him what was going on, and he said, « I feel so at peace, » even though he was still addicted to heroin. We had done heroin together in the past, but I had stopped, unlike Eddie.

In 1994, you also appeared on Dave Stewart’s album Greetings From the Gutter, and you recorded your album Fresh Mud together in 2006. How did you join him?

Dave Stewart is the best music industry professional I’ve ever worked with. Bootsy had started a project with him, and then Dave Stewart recorded the album Greetings From the Gutter. At the time, I went to see the kids who lived in Cincinnati. Bootsy called me to explain that he was working on a solo album and Dave Stewart’s album. I didn’t know who he was, but Bootsy told me he was the guy from Eurythmics, the one you see playing guitar in the videos. Of course, I knew Annie Lennox, and Bootsy told me that Dave was responsible for the concept of the band, the production, and even Annie Lennox’s look. He asked me if I wanted to come and sing on his project. So I flew out with Henry Benifield, the other singer in the Rubber Band at the time, and we flew out to London and sang on one

song, the single “Jealousy.”

I flew back to Paris, where I was living at the time, and a few days later I got a call from Dave Stewart’s office. Apparently he really liked what I had done

and he wanted to meet me again. He was going to play a show in Paris with his band the night I was coming back from Germany after a Grand Slam show. I found myself backstage and as I was about to go on stage, Dave Stewart saw me and invited me up. I declined because I had no idea what they were going to play. He just said, “It’s okay. You can come up whenever you want.” The show was exclusive, but at one point I felt a bit of a drop in energy. I went up to a microphone and sang a few choruses, then went back behind the curtain. Then I came back a couple of times, and Dave seemed to like it. After the show, he arranged to meet me at his hotel the next day. His daughter, who was very young, was with us in the hotel restaurant, and Dave asked me to sing a song for her. After that, he said, « I’d

like to record a duet album with you. We’d do 50/50, like Annie in Eurythmics. »

A few weeks later, we ended up at his studio in London and recorded six songs in three days and three nights, and that’s how the Fresh Mud album was born. One day, he showed up at the studio fifteen minutes late. He apologised, but I found out soon after that he had put a large sum of money into my bank account. We didn’t have a contract yet, but Dave just wanted me to feel comfortable with the project. Later, he offered me and my wife to move into a house on his property in Hazlemere, England. Thanks to him, I was able to meet Michael Jackson, Mick Jagger with whom I sang on the Alfie soundtrack, and Bob Dylan, who also plays piano on Fresh Mud.

You are now 70 years old, but you continue to work on studio and live projects.

I will stop when I am dead (laughs)! I know a lot of musicians my age, and some are unfortunately not in good health. Others look very old and their sound is dated. I don’t know what being 70 years old means. Every morning, I wake up and I feel good. I am still Mudbone.

One last question: where does your nickname Mudbone come from?

Bootsy came up with it. He was a big fan of Richard Pryor, and he told me one day that I reminded him of one of his characters named Mudbone, a country boy from Tupelo, Mississippi, and it stuck. The first time I met Chaka Khan, Bootsy introduced me by saying, “Chaka, this is Mudbone, my singer.” I told Chaka, “My real name is Gary Cooper,” and she said, “Oh, hi, Mudbone.” It’s hard to go back after that (laughs)! At first I took it as a joke, but because of my vocal style and my look, it became my signature and I’m very proud of it.

Interview : Christophe Geudin. Portraits : Sabrina Mariez